When someone with Parkinson’s disease starts seeing things that aren’t there-people in the room, shadows moving, or loved ones who have passed away-it’s terrifying. Not just for them, but for everyone around them. This is Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDP), and it’s one of the most common reasons patients end up in the hospital. About 1 in 4 Parkinson’s hospitalizations are due to psychosis, according to the Parkinson’s Foundation. But here’s the cruel twist: the very drugs doctors reach for to treat these hallucinations and delusions can make the shaking, stiffness, and slow movement even worse.

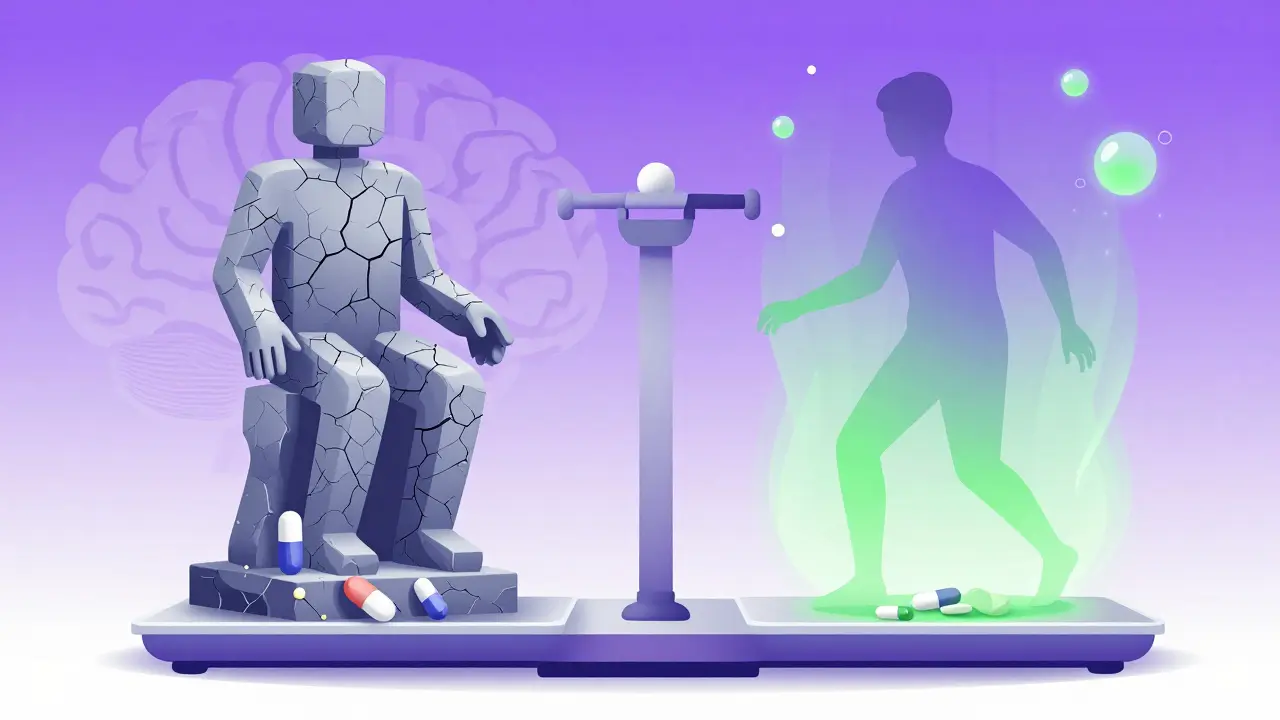

The Dopamine Dilemma

Parkinson’s disease is caused by the slow death of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain. Dopamine isn’t just about mood-it’s the chemical that helps your body move smoothly. Without enough of it, you get tremors, rigid muscles, and trouble starting to walk. That’s why levodopa, a dopamine replacement, is the main treatment. Antipsychotics work by blocking dopamine receptors, especially the D2 type. That’s how they calm down overactive brain signals in schizophrenia. But in Parkinson’s, you’re already low on dopamine. Blocking what’s left is like turning off the last few drops of water from a nearly empty tank. The result? Motor symptoms spike. Bradykinesia gets slower. Rigidity tightens. Falls become more frequent. This isn’t a guess. It’s been documented since the 1970s. In 1996, the American Academy of Neurology first warned that typical antipsychotics could trigger severe parkinsonism. By 2015, they confirmed it with strong evidence: clozapine reduces psychosis without worsening movement. Other drugs? Not so much.Which Antipsychotics Are Dangerous?

Not all antipsychotics are created equal. First-generation drugs-like haloperidol, fluphenazine, and chlorpromazine-are the worst offenders. Haloperidol, often called Haldol, blocks 90-100% of D2 receptors at standard doses. In Parkinson’s patients, even 0.25 mg a day can trigger a dramatic decline in mobility. Studies show 70-80% of patients on haloperidol develop severe parkinsonism. The Parkinson’s Foundation says these drugs should be avoided entirely. Risperidone is another problem. A 2005 double-blind trial found it reduced psychosis almost as well as clozapine-but it made motor symptoms 4 times worse. Patients on risperidone saw their UPDRS-III scores (a standard motor assessment) jump by an average of 7.2 points. That’s like going from mild stiffness to needing help walking. Worse, a 2013 Canadian study found risperidone nearly doubled the risk of death in Parkinson’s patients. Olanzapine? Same story. One study of 12 patients showed 75% got worse motor function, and only one stayed on the drug. Even low doses of risperidone (0.5 mg) sometimes avoid motor harm-but the risk is too high to gamble with.What’s Safer? Clozapine and Quetiapine

There are two antipsychotics that don’t wreck motor control: clozapine and quetiapine. Clozapine, approved by the FDA for PDP in 2016, blocks only 40-60% of D2 receptors. It also hits serotonin receptors, which helps balance out the dopamine blockade. In clinical trials, clozapine improved psychosis without making movement worse. In fact, motor scores barely budged-just 1.8 points higher on UPDRS-III compared to 7.2 with risperidone. But clozapine has a catch: it can cause agranulocytosis, a dangerous drop in white blood cells. That’s why patients on clozapine need weekly blood tests. If the absolute neutrophil count falls below 1,500 cells/μL, the drug must stop. It’s a hassle, but it’s safer than letting motor symptoms spiral. Quetiapine (Seroquel) is used off-label. It’s less potent than clozapine, but it’s easier to start. Doses are low-12.5 to 25 mg at night-and most people see improvement in 1-2 weeks. The problem? Evidence is mixed. Some studies show it works. Others, like a 2017 trial by Factor et al., found no difference between quetiapine and placebo. Still, many neurologists use it because it’s safer than risperidone or haloperidol. The American Academy of Neurology gives it Level C evidence-meaning it’s probably helpful, but not proven beyond doubt.

Pimavanserin: The First Non-Dopaminergic Option

In April 2022, the FDA approved pimavanserin (Nuplazid), the first antipsychotic that doesn’t block dopamine at all. It works by targeting serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. In the 2014-020 trial, patients saw a 5.79-point drop in hallucinations with no worsening of motor symptoms. That’s huge. But there’s a dark side. Post-marketing data showed a 1.7-fold increase in death risk compared to placebo. The FDA slapped on a black box warning-the strongest kind. It’s still used, but only after safer options fail. Many doctors avoid it unless the patient is at high risk of falls or has tried everything else.The New Hope: Lumateperone

The most promising drug on the horizon is lumateperone. It’s another serotonin-dopamine modulator, designed to avoid motor side effects. The HARMONY trial, still ongoing as of early 2024, showed a 3.4-point improvement in psychosis with no motor decline after 42 weeks. Final results are expected in Q2 2024. If confirmed, this could become the new standard-effective, safe, and without the blood monitoring nightmare of clozapine.What to Do Before Reaching for Antipsychotics

Before you even think about an antipsychotic, try this: adjust the Parkinson’s meds. Many psychosis cases are triggered by too much dopamine stimulation. Dopamine agonists like pramipexole or ropinirole are common culprits. So are anticholinergics, amantadine, and COMT inhibitors. A 2018 study found that 62% of patients with PDP saw their hallucinations disappear just by simplifying their medication list-no antipsychotics needed. Start by cutting back on dopamine agonists. Then reduce anticholinergics. Lower amantadine. Taper COMT inhibitors. Only after all that fails should you consider an antipsychotic.

Monitoring and Safety

If you do start clozapine or quetiapine, monitor closely. Check UPDRS-III scores every two weeks. If motor function drops by more than 30% from baseline, stop the drug. That’s the 2019 Movement Disorder Society guideline. Also, watch for sedation, low blood pressure, and confusion-common side effects. Elderly patients are especially vulnerable. Doses should be tiny: clozapine starts at 6.25 mg at night. Quetiapine at 12.5 mg. Go slow. Let the brain adjust.The Bottom Line

Treating psychosis in Parkinson’s isn’t about finding the strongest antipsychotic. It’s about finding the least harmful one. Haloperidol and risperidone are dangerous. Clozapine works but needs blood tests. Quetiapine is a middle ground. Pimavanserin helps but carries a death risk. Lumateperone may be the answer we’ve been waiting for. The real win? Avoiding antipsychotics altogether by tweaking Parkinson’s meds first. Most patients don’t need them. And when they do, the goal isn’t to eliminate hallucinations completely-it’s to make them manageable without making walking impossible.Frequently Asked Questions

Can antipsychotics cause Parkinson’s disease?

No, antipsychotics don’t cause Parkinson’s disease. But they can trigger drug-induced parkinsonism-a condition that looks just like Parkinson’s, with tremors, stiffness, and slow movement. This usually goes away when the drug is stopped. In people who already have Parkinson’s, antipsychotics make existing symptoms much worse, not create new ones.

Is there a safe antipsychotic for Parkinson’s patients?

Yes-clozapine is the only one FDA-approved for Parkinson’s psychosis, and it doesn’t worsen motor symptoms in most patients. Quetiapine is used off-label and is generally safer than other antipsychotics, though evidence is weaker. Both require low doses and careful monitoring. Avoid haloperidol, risperidone, and olanzapine-they’re too risky.

Why is clozapine not used more often if it’s so effective?

Because it can cause agranulocytosis-a rare but life-threatening drop in white blood cells. Patients need weekly blood tests for the first 6 months, then every two weeks. Many doctors avoid it because of the monitoring burden, and many patients find it hard to stick with. But for those who can tolerate it, it’s the gold standard.

Can hallucinations in Parkinson’s be treated without drugs?

Yes. In over 60% of cases, hallucinations improve or disappear by adjusting Parkinson’s medications-like reducing dopamine agonists, anticholinergics, or amantadine. Non-drug approaches like improving sleep, reducing nighttime light exposure, and increasing daytime activity also help. Sometimes, just talking to the patient about what they’re seeing reduces distress without any medication.

What should I do if a loved one with Parkinson’s starts seeing things?

Don’t panic. Don’t rush to an antipsychotic. First, review their medication list with their neurologist. Cut back on dopamine agonists or anticholinergics. Improve sleep hygiene. Reduce alcohol and sedatives. If symptoms persist after 4-6 weeks, talk about clozapine or quetiapine. Never start haloperidol or risperidone. Document the hallucinations-what they see, when, and how often. That helps the doctor decide if it’s truly psychosis or just misperception.

Lauren Wall

January 22, 2026 AT 16:46