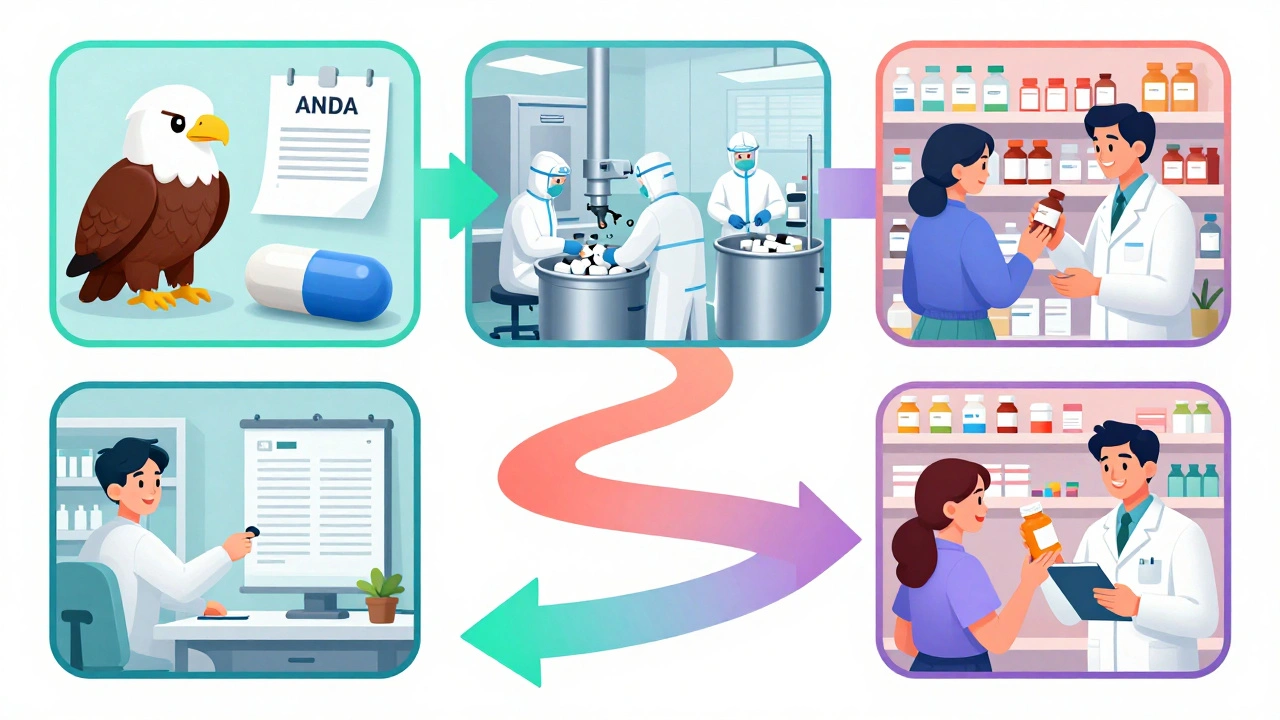

Every time you pick up a bottle of generic ibuprofen at the corner pharmacy, you’re holding the result of a complex, tightly regulated journey that starts long before the pills are even packaged. This journey begins with an ANDA-the Abbreviated New Drug Application-and ends with a shelf in your local CVS or Walgreens. But what happens in between? How does a drug move from a lab in India or a factory in New Jersey to the hands of a patient paying 85% less than the brand name? It’s not just about getting FDA approval. It’s about navigating manufacturing, contracts, logistics, and payer politics-all before a single pill hits the counter.

What Is an ANDA, and Why Does It Matter?

The ANDA is the legal gateway for generic drugs to enter the U.S. market. Created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984, it lets manufacturers skip the expensive, years-long clinical trials that brand-name companies must run. Instead, they prove their version is bioequivalent-meaning it delivers the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the original drug. No need to re-prove safety or effectiveness. Just prove it works the same way. The FDA doesn’t just rubber-stamp these applications. Each ANDA must include detailed data on chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC). That means showing exactly how the drug is made, what equipment is used, how batches are tested, and how quality is maintained. Even small changes in the manufacturing process can trigger a rejection. In fact, about 40% of initial ANDA submissions get a Complete Response Letter from the FDA-meaning they’re incomplete or flawed. Most applicants need to go through at least one revision cycle before approval. The approval timeline? On average, 30 months. But that’s not the whole story. Some applications get priority status. If a drug is in short supply, or if it’s the first generic version of a popular brand (like EpiPen or Lipitor), the FDA fast-tracks it. In 2022 alone, 112 first generics were approved-drugs with combined sales of $39 billion. These are the ones that make the biggest impact on prices.The Manufacturing Leap: From Lab to Large-Scale Production

Getting FDA approval doesn’t mean you can start shipping boxes to pharmacies. Now comes the real challenge: scaling up. A drug might have been made in small batches during testing. But retail pharmacies need millions of pills. That means reconfiguring entire production lines, training new staff, validating equipment under real-world conditions, and ensuring every batch meets the same strict standards. This transition from pilot scale to commercial volume typically takes 60 to 120 days. For simple pills, this is manageable. But for complex products-like inhalers, transdermal patches, or injectables-it’s a whole different ballgame. These require precise delivery systems. A change in the propellant in an inhaler, or the adhesive in a patch, can alter how the drug is absorbed. The FDA treats these as high-risk products. Approval rates for complex generics are only about 65%, compared to 85% for standard tablets. Manufacturers also have to prove their facilities meet current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). The FDA inspects these sites-sometimes unannounced. And if a facility is overseas, as many are, inspections become even more complicated. A single failed inspection can delay a launch by months.Getting Into the Payer System: The Hidden Battle

Here’s where most people don’t realize the fight begins: with pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). These are the middlemen between drugmakers, insurers, and pharmacies. They decide which drugs get placed on which “tier” of a formulary. If your generic is on Tier 1-the preferred list-it’ll be the first one a pharmacist recommends. If it’s on Tier 2 or 3, the patient might pay more out of pocket, and the pharmacy might not even stock it. To get on Tier 1, generic manufacturers have to offer deep discounts-often 20% to 30% lower than their initial price projections. A 2022 survey of 45 generic manufacturers found that 78% said securing PBM contracts was harder than getting FDA approval. One senior sourcing manager on Reddit described it this way: “You can have the best generic on the market, but if Express Scripts or OptumRx doesn’t list it as preferred, you’re invisible.” Negotiations can take 30 to 90 days. And they’re not just about price. PBMs also demand rebates, marketing support, and sometimes exclusivity deals. If you’re a small generic company without a big sales team, this can be a dealbreaker.

Distribution: Getting the Drug to the Pharmacy

Once the PBM says yes, the drug still has to physically get to the pharmacy. That’s where the big wholesalers come in: AmerisourceBergen, McKesson, and Cardinal Health. These companies distribute over 80% of all prescription drugs in the U.S. Getting added to their systems isn’t automatic. The manufacturer has to provide product data, pricing, barcodes, and compliance documentation. The wholesaler then has to update their inventory software, train their warehouse staff, and route the product through their distribution network. This usually takes 15 to 30 days. For smaller pharmacies that buy directly from manufacturers, the process can be even slower. They don’t have the volume to justify immediate stocking. So even if the wholesaler has the drug, the local pharmacy might not order it until a patient asks for it.The Final Step: Pharmacy Systems and Staff

Even when the drug arrives at the pharmacy, it’s not instantly ready to sell. Pharmacists use software systems to manage inventory and prescriptions. Each new drug has to be entered into the system with the correct National Drug Code (NDC), dosage, and pricing. That’s a manual process-and pharmacies are busy. Many pharmacies wait until they have at least a few prescriptions lined up before adding a new generic. They don’t want to tie up cash on inventory that won’t sell. So even if the drug is approved, contracted, and shipped, it might sit in a warehouse for weeks before a pharmacist finally enters it into their system. On average, it takes 112 days from FDA approval to the first retail dispensing. But that number varies. Cardiovascular generics-like generic atorvastatin-move faster, averaging 87 days. Complex drugs like inhaled corticosteroids can take over 145 days.

Saurabh Tiwari

December 2, 2025 AT 16:05