QTc Interval Calculator

The QTc interval corrects the raw QT interval for heart rate. Using the Fridericia formula (QTc = QT / ∛RR) provides a more accurate assessment than Bazett's formula, especially at higher heart rates. This calculator helps determine if your QTc interval is within safe limits.

Fridericia formula: QTc = QT / ∛RR

Result:

When you take an antibiotic like ciprofloxacin or azithromycin, you’re usually thinking about clearing up an infection-not about your heart. But for some people, these common drugs can quietly disrupt the electrical rhythm of the heart, leading to a dangerous condition called QT prolongation. This isn’t rare. It’s not theoretical. It’s something that happens in hospitals, nursing homes, and even in outpatient clinics every day. And if you’re over 65, female, taking other medications, or have kidney or heart problems, your risk goes up fast.

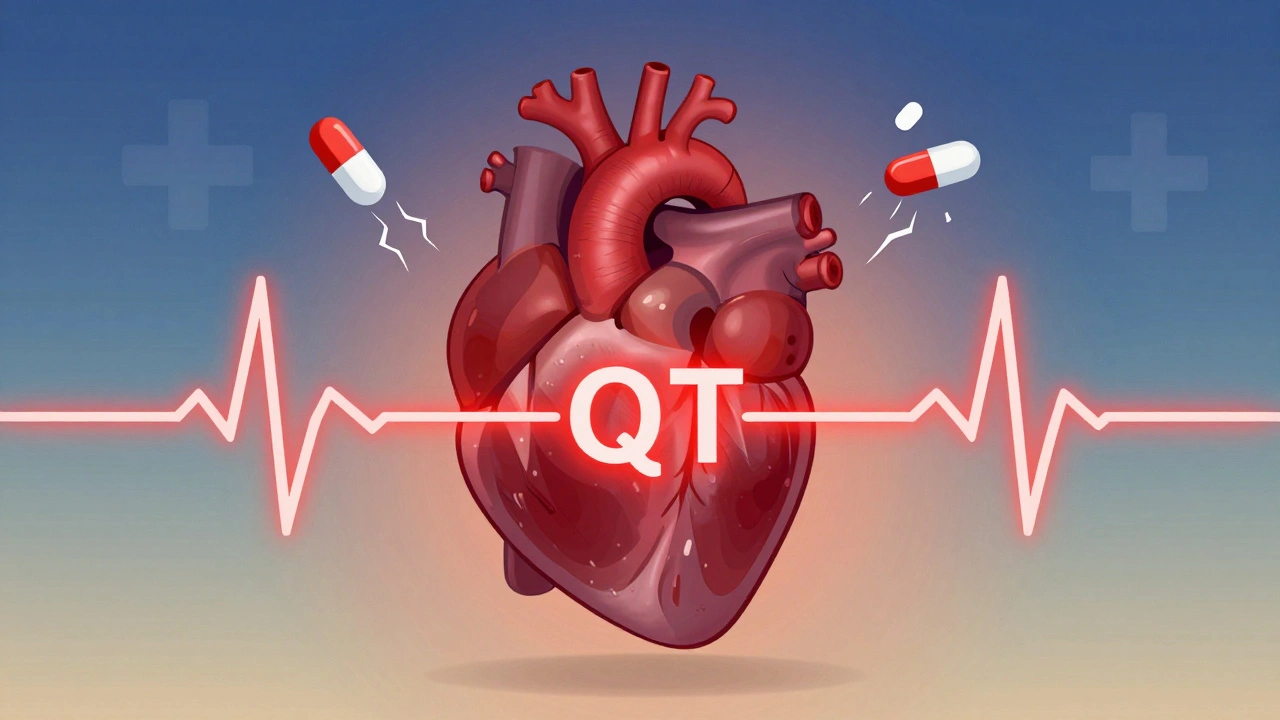

What QT Prolongation Really Means

Your heart beats because of electrical signals. The QT interval on an ECG shows how long it takes for the lower chambers of your heart to recharge after each beat. If that interval gets too long, your heart can slip into a chaotic rhythm called Torsades de Pointes. It’s a type of ventricular arrhythmia that can turn into sudden cardiac arrest. You don’t always feel it coming. No chest pain. No dizziness. Just-suddenly-your heart stops. Fluoroquinolones (like ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin) and macrolides (like erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin) both block a specific potassium channel in heart cells called hERG. This slows down the heart’s ability to reset after beating. It’s the same mechanism used by some antiarrhythmic drugs-but when it happens accidentally from an antibiotic, it’s dangerous. The FDA has issued multiple warnings about this. In 2013, they added a black box warning to fluoroquinolones after reviewing hundreds of cases linking them to life-threatening heart rhythms. Erythromycin, one of the oldest macrolides, was flagged even earlier. And yet, these drugs are still prescribed daily, often without checking the patient’s heart first.Not All Antibiotics Are Created Equal

If you’re told you need an antibiotic, not all options carry the same heart risk. Here’s how they stack up:- High risk: Sparfloxacin (withdrawn), grepafloxacin (never sold in the U.S.), erythromycin

- Moderate risk: Moxifloxacin, clarithromycin

- Low risk: Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin

- Minimal risk: Azithromycin

Who’s at Real Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it. QT prolongation doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s the result of a perfect storm of risk factors:- Age over 65

- Female gender (women have 2-3 times higher risk of Torsades)

- Existing heart disease (heart failure, low ejection fraction, past heart attack)

- Low potassium or magnesium levels

- Kidney or liver disease (slows drug clearance)

- Taking other QT-prolonging drugs (antiarrhythmics, antidepressants, antifungals)

- Family history of long QT syndrome

- Slow heart rate (below 50 bpm)

How to Monitor for QT Prolongation

Monitoring isn’t optional. It’s standard of care-for the right patients. The British Thoracic Society guidelines (2023) are clear: Before starting any macrolide, get an ECG. And not just any ECG. You need the QTc interval-corrected for heart rate. The best way to do that? Use the Fridericia formula: QTc = QT / ∛RR. It’s more accurate than the old Bazett formula, especially at higher heart rates. Bazett can mislead you by overcorrecting when the heart is racing. For macrolides:- Do a baseline ECG before starting treatment.

- Check again at 1 month.

- Stop the drug if QTc exceeds 500 ms, or increases by more than 60 ms from baseline.

- Get an ECG 7-15 days after starting.

- Repeat monthly for the first 3 months.

- Continue periodic checks if you’re on long-term therapy.

What to Do If QT Prolongation Shows Up

If your ECG shows QTc >500 ms, or a rise of more than 60 ms from baseline, stop the antibiotic immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t “see how it goes.” Then fix what you can:- Check potassium and magnesium. Aim for potassium above 4.0 mmol/L and magnesium above 2.0 mg/dL. Low levels make everything worse.

- Stop any other QT-prolonging drugs if possible.

- Don’t give more of the same antibiotic, even at a lower dose.

- Consider switching to a safer alternative: amoxicillin, doxycycline, or nitrofurantoin (for UTIs) instead of fluoroquinolones.

Why This Matters in Real Life

In a nursing home in Cambridge, a 72-year-old woman with mild kidney disease and low potassium was prescribed levofloxacin for a UTI. She was also on a diuretic and had a history of atrial fibrillation. No ECG was done. Three days later, she collapsed. She survived-but barely. The QTc had jumped from 440 ms to 580 ms. That’s not an outlier. That’s typical. A 2025 study from the Canadian Network for Observational Drug Effect Studies found that nearly 1 in 12 older adults prescribed fluoroquinolones for uncomplicated infections had a dangerous QT prolongation event within 30 days. The problem isn’t the drugs themselves. It’s how we use them. Fluoroquinolones are often prescribed for simple UTIs, sinus infections, or bronchitis-conditions that usually resolve on their own or with safer antibiotics. But because they’re broad-spectrum and cheap, they’re overused. And the heart pays the price.What You Can Do

If you’re prescribed a fluoroquinolone or macrolide:- Ask: “Is this the safest option for my heart?”

- Ask: “Can you check my potassium and magnesium?”

- Ask: “Will you do an ECG before and after I start this?”

- Know your risk factors. If you’re over 65, female, on multiple meds, or have heart or kidney issues-push back if you’re not being monitored.

- Use the Fridericia formula for QTc, not Bazett’s.

- Don’t assume “low risk” means “no risk.”

- Check for drug interactions-especially with antifungals, antidepressants, and diuretics.

- Document your reasoning. If you choose a higher-risk drug, note why-and that you’ve assessed cardiac risk.

Alternatives to High-Risk Antibiotics

For common infections, safer choices exist:- Uncomplicated UTI: Nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin, amoxicillin-clavulanate

- Sinusitis: Amoxicillin, doxycycline

- Community-acquired pneumonia: Amoxicillin, doxycycline, or azithromycin (low risk)

- Skin infection: Cephalexin, clindamycin

Future of Monitoring

We’re starting to see smarter tools. Some hospitals are testing AI-powered ECG algorithms that flag QT prolongation automatically. Others are building digital risk calculators that weigh age, sex, kidney function, and meds to predict who needs monitoring. But right now, the best tool is still the ECG-and the willingness to use it. No algorithm replaces a thoughtful clinician who asks: Is this drug worth the risk?Final Takeaway

Antibiotics save lives. But they’re not harmless. Fluoroquinolones and macrolides are powerful-but they carry a hidden cardiac risk that’s easy to miss. The solution isn’t to avoid them entirely. It’s to use them wisely. Know your patient. Know the drug. Know the risk. Check the ECG. Correct the electrolytes. Choose the safest alternative. And never assume that because a drug is common, it’s safe.Can azithromycin cause QT prolongation?

Yes, but the risk is much lower than with erythromycin or clarithromycin. Azithromycin has minimal hERG channel blockade compared to other macrolides. Most guidelines consider it low-risk for QT prolongation, especially in healthy individuals. However, in patients with multiple risk factors-like older age, low potassium, heart disease, or taking other QT-prolonging drugs-it can still contribute to dangerous rhythms. Always check baseline ECG in high-risk patients before starting any macrolide.

What’s the difference between QT and QTc?

QT is the raw measurement of the interval on the ECG. QTc (corrected QT) adjusts that number for heart rate. A fast heart rate shortens QT naturally; a slow heart rate lengthens it. QTc lets doctors compare results across different heart rates. Without correction, you can’t tell if the interval is truly prolonged or just affected by how fast the heart is beating. Always use QTc for clinical decisions.

Why is the Fridericia formula better than Bazett’s?

Bazett’s formula (QTc = QT / √RR) overcorrects at high heart rates and undercorrects at low ones. This means it can falsely make a normal QT look long-or miss a dangerous one. Fridericia’s formula (QTc = QT / ∛RR) adjusts more accurately across all heart rates. Studies show it predicts death and arrhythmias better. In 2023, the British Thoracic Society recommended Fridericia as the standard for clinical use. If your ECG report uses Bazett’s, ask for Fridericia.

Can QT prolongation be reversed?

Yes, if caught early. Stopping the offending drug is the first step. Correcting low potassium or magnesium levels often brings the QTc back to normal within days. In severe cases, IV magnesium sulfate is given as an emergency treatment. But if Torsades de Pointes develops, it can lead to cardiac arrest. That’s why monitoring and early intervention are critical-once the arrhythmia starts, it’s harder to reverse.

Should I avoid fluoroquinolones completely?

No-but you should avoid them for simple infections. The FDA and major guidelines now recommend fluoroquinolones only for serious infections like anthrax, plague, or complicated UTIs when no safer option exists. For uncomplicated UTIs, sinusitis, or bronchitis, they’re rarely needed. Amoxicillin, nitrofurantoin, or doxycycline are safer and just as effective. Don’t take fluoroquinolones unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk to your heart.

How often should I get an ECG if I’m on these antibiotics?

For macrolides: one ECG before starting, and another at 1 month. For fluoroquinolones: ECG at 7-15 days after starting, then monthly for the first 3 months. If you have risk factors-like age, kidney disease, or other meds-you may need more frequent checks. If your QTc stays normal after 3 months, less frequent monitoring is usually safe. Always follow your doctor’s advice based on your personal risk profile.

Lola Bchoudi

December 9, 2025 AT 01:26