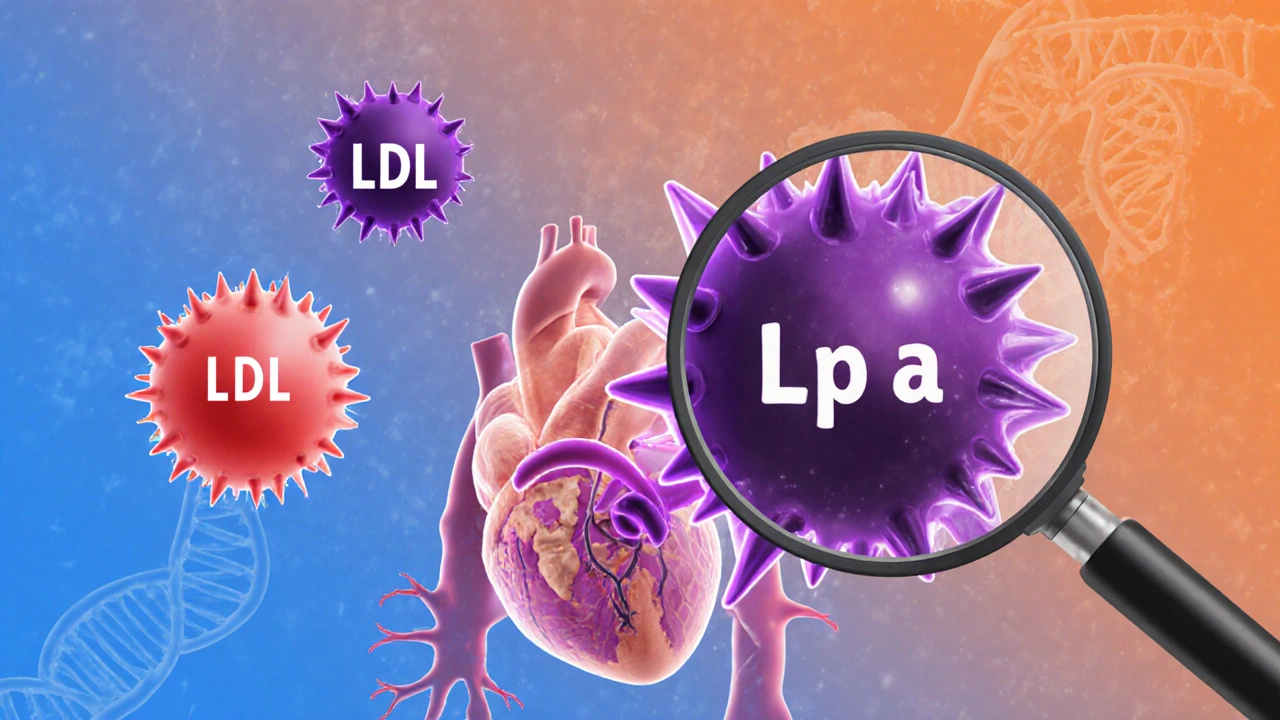

Most people know about LDL cholesterol - the "bad" kind that clogs arteries. But there’s another silent player in heart disease that doesn’t show up on routine blood tests: lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). It’s not caused by poor diet or lack of exercise. It’s written into your genes. And if you have high levels, your risk of heart attack, stroke, or aortic valve disease can be just as high as someone with inherited high cholesterol - even if everything else looks normal.

What Is Lipoprotein(a), Really?

Lp(a) is a special type of cholesterol-carrying particle. Think of it like an LDL particle with an extra protein glued on - apolipoprotein(a). That extra piece isn’t just decoration. It makes Lp(a) sticky and dangerous. It sticks to damaged areas in your arteries, helping build plaque. It also interferes with your body’s natural ability to break down blood clots, making heart attacks and strokes more likely.

Unlike regular cholesterol, Lp(a) levels don’t change much with what you eat or how much you work out. That’s because 70% to 90% of your Lp(a) level is controlled by your genes - specifically, variations in the LPA gene. This makes it one of the most heritable risk factors for heart disease we know of. If your parent has high Lp(a), you have a 50% chance of inheriting it.

It’s not rare. About one in five people worldwide - 20% - have levels high enough to raise their cardiovascular risk. Yet most doctors never test for it. Why? Because it’s not part of a standard lipid panel. You have to ask for it.

How High Is Too High?

Lp(a) is measured in either milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or nanomoles per liter (nmol/L). The conversion between them is precise: nmol/L = 2.18 × mg/dL - 3.83. But here’s what matters clinically:

- 50 mg/dL (105 nmol/L) or higher = increased risk of heart attack or stroke

- 90 mg/dL (190 nmol/L) or higher = severe risk, similar to familial hypercholesterolemia

- 130-391 mg/dL (280-849 nmol/L) = risk equivalent to having a genetic cholesterol disorder

These numbers aren’t guesses. They’re based on large studies tracking thousands of people over decades. People with Lp(a) above 50 mg/dL have up to a 3-fold higher risk of heart disease - even if their LDL is perfectly normal.

Who Should Get Tested?

If you’ve had a heart attack before age 55 (men) or 65 (women), or if someone in your family has, you should get tested. Same if you have:

- Familial hypercholesterolemia

- Aortic valve stenosis (narrowing of the heart’s main valve)

- Early coronary artery disease with no obvious cause

- Strong family history of sudden cardiac death

But here’s the thing: many people with high Lp(a) have no symptoms until something serious happens. That’s why experts like Dr. Gregory Schwartz at the University of Colorado now recommend everyone get tested at least once in their lifetime. It’s a simple blood test. No fasting needed. Just ask your doctor.

Why It’s Worse for Some Groups

Lp(a) doesn’t affect everyone equally. Black individuals tend to have higher levels on average than white, Hispanic, or Asian populations. Women often see their Lp(a) rise after menopause, likely because estrogen - which helps keep Lp(a) low - drops. That’s one reason why heart disease risk jumps in women after 50.

But here’s the critical point: regardless of your race, gender, or background, the higher your Lp(a), the higher your risk. No exceptions.

What Doesn’t Work (And Why)

Most people assume if you have high cholesterol, you just need to eat less fat, lose weight, and exercise. That works for LDL. It doesn’t work for Lp(a).

Statins - the go-to cholesterol drugs - barely touch Lp(a). In fact, they might slightly raise it. Niacin (vitamin B3) can lower Lp(a) by 20-30%, but it causes flushing, liver problems, and doesn’t clearly reduce heart attacks. So it’s rarely used.

Dietary changes? No meaningful effect. Exercise? Doesn’t lower Lp(a). Weight loss? Doesn’t help. This is frustrating for patients who do everything "right" and still face high risk.

What Does Work - Now and Soon

Right now, the best strategy is aggressive management of other risk factors. Lower your LDL with statins or PCSK9 inhibitors. Control blood pressure. Don’t smoke. Manage diabetes. These steps won’t touch your Lp(a), but they reduce the overall burden on your arteries.

But the real game-changer is coming. A new class of drugs called antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) is showing dramatic results. One drug, pelacarsen, lowers Lp(a) by up to 80% in clinical trials. It’s not approved yet, but the final phase 3 trial - called Lp(a) HORIZON - is tracking whether lowering Lp(a) actually prevents heart attacks and strokes. Results are expected in late 2025.

If the trial succeeds, pelacarsen could become the first treatment specifically designed to target Lp(a). This would be a historic shift - turning a genetic risk into something we can actively treat.

What You Can Do Today

Even without a cure, knowledge is power. If you know your Lp(a) is high:

- Get your LDL under control - aim for below 70 mg/dL if you’re at high risk

- Ask about PCSK9 inhibitors if statins aren’t enough

- Keep your blood pressure under 120/80

- Don’t smoke - it’s especially dangerous when Lp(a) is high

- Get checked for aortic valve disease - Lp(a) is a major cause

- Tell your close family members - they should get tested too

There’s no magic pill yet. But you’re not powerless. You can reduce your total risk significantly by controlling what you can.

The Bigger Picture

Lp(a) has been ignored for decades because testing was messy and no treatment existed. But science has caught up. We now know it’s not just a marker - it’s a direct cause of heart disease. And we’re on the brink of the first therapy that can target it.

For millions of people with high Lp(a), this isn’t just about cholesterol. It’s about breaking a genetic curse. It’s about giving people who did everything right a real shot at a healthy heart. The next 12 months could change everything.

If you’ve ever been told, "Your numbers are fine," but still felt something was off - ask for the Lp(a) test. It might be the most important blood test you ever get.

Is lipoprotein(a) the same as LDL cholesterol?

No. Lp(a) is a separate lipoprotein particle that contains an LDL-like core but has an extra protein called apolipoprotein(a) attached. While both carry cholesterol, Lp(a) is genetically determined and contributes to heart disease in unique ways - like promoting blood clots and inflammation - that LDL doesn’t.

Can diet and exercise lower lipoprotein(a)?

No. Unlike LDL or triglycerides, Lp(a) levels are not meaningfully changed by diet, exercise, weight loss, or most lifestyle changes. That’s because over 90% of your Lp(a) level is controlled by your genes. However, healthy habits still matter - they reduce your overall cardiovascular risk.

Should everyone get tested for Lp(a)?

Experts increasingly say yes. While testing is still not routine, organizations like the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology recommend at least one Lp(a) test in adulthood - especially if you have a personal or family history of early heart disease, stroke, or high cholesterol. It’s a simple blood test that can reveal hidden risk.

Is high Lp(a) dangerous even if my other cholesterol numbers are normal?

Yes. High Lp(a) is an independent risk factor. You can have perfect LDL, HDL, and triglyceride levels and still be at high risk for heart attack or stroke if your Lp(a) is elevated. That’s why it’s called a "hidden" risk - it doesn’t show up on standard panels.

Will new drugs for Lp(a) be available soon?

The most promising drug, pelacarsen, is in the final stage of testing (phase 3). Results from the Lp(a) HORIZON trial are expected in 2025. If successful, this could lead to the first FDA-approved treatment specifically designed to lower Lp(a) and reduce heart events - a major breakthrough for people with this genetic risk.

Can I inherit high Lp(a) from my parents?

Yes. High Lp(a) is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. If one parent has high levels, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it. That’s why family history is so important - if a parent had a heart attack in their 40s or 50s, Lp(a) could be the hidden cause.

Does Lp(a) affect women differently than men?

Yes. Estrogen helps suppress Lp(a) levels. After menopause, when estrogen drops, many women see their Lp(a) rise significantly. This contributes to the increased risk of heart disease in women after age 50. Men typically have stable levels throughout adulthood, but they can still have very high levels from birth.

Is Lp(a) more common in certain ethnic groups?

Yes. People of African descent tend to have the highest average Lp(a) levels globally, followed by South Asians. Levels are generally lower in white, Hispanic, and East Asian populations. But regardless of ethnicity, higher levels mean higher risk - and everyone should be aware of their numbers.

Debanjan Banerjee

November 20, 2025 AT 20:41