When your heart valve doesn’t open or close right, your whole body feels it. You might not notice at first-just a little shortness of breath climbing stairs, or getting tired faster than usual. But if one of your heart’s four valves-mitral, aortic, tricuspid, or pulmonary-is narrowed (stenosis) or leaking (regurgitation), the strain builds up quietly. Left untreated, it can lead to heart failure, irregular rhythms, or even sudden death. The good news? We know exactly how to fix this now, and the options are better than ever.

What Happens When Heart Valves Fail

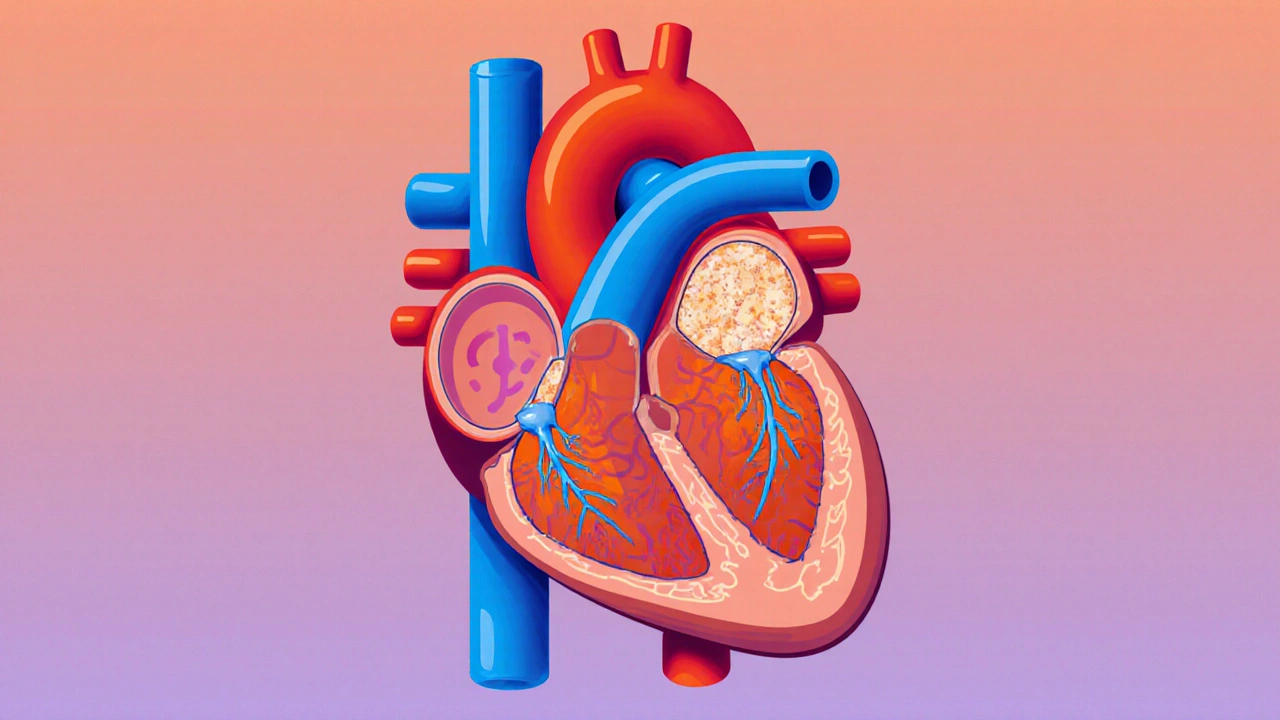

Your heart has four valves that act like one-way doors. They open to let blood flow forward and snap shut to stop it from flowing back. When a valve becomes stiff and can’t open fully, it’s called stenosis. When it doesn’t close tight and blood leaks backward, it’s regurgitation. Both force your heart to work harder, and over time, that wear and tear damages the muscle. Aortic stenosis is the most common serious valve problem in older adults. About 2% of people over 65 have it, mostly because calcium builds up on the valve leaflets over decades. In younger people, it’s often linked to a bicuspid aortic valve-a birth defect where the valve has only two leaflets instead of three. This affects 1-2% of the population and can lead to stenosis decades earlier than normal. Mitral stenosis is rarer in the UK and US, but still common worldwide. Around 80% of cases come from rheumatic fever, which was once widespread but is now rare in high-income countries thanks to antibiotics. Still, in places with limited healthcare access, it’s a major cause of valve disease. Regurgitation works differently. In aortic regurgitation, blood leaks back into the left ventricle after each heartbeat. In mitral regurgitation, blood flows backward into the left atrium. The heart compensates by getting bigger, but eventually, it can’t keep up. Symptoms like fatigue, palpitations, and swelling in the legs show up slowly. Many people ignore them until they can’t walk across the room without stopping.Stenosis vs. Regurgitation: Key Differences

It’s easy to mix up stenosis and regurgitation because both cause similar symptoms. But they damage the heart in opposite ways. In stenosis, the valve opening is too small. The heart must pump harder to push blood through. That leads to thickening of the heart muscle, high pressure in the chambers, and eventually, chest pain, dizziness, or fainting. Severe aortic stenosis is defined by a valve area smaller than 1.0 cm², a pressure gradient over 40 mmHg, and blood flow speed above 4.0 m/s. At that point, survival drops sharply without treatment. In regurgitation, the valve leaks. The heart has to pump extra blood each time to make up for what’s flowing backward. This causes volume overload. The left ventricle stretches out, and symptoms like shortness of breath and fatigue appear earlier than in stenosis. Mitral regurgitation, especially if it’s functional (caused by heart muscle weakness), can be tricky to treat because the valve itself isn’t broken-just the heart around it is. The symptoms tell the story. Aortic stenosis patients often report the classic triad: chest pain (54%), fainting (33%), and heart failure (48%). Aortic regurgitation patients more often feel their heart racing (29%) or get winded during light activity (71%). Mitral stenosis causes fluid buildup in the lungs, leading to trouble breathing when lying down. Mitral regurgitation? Most people just feel exhausted-79% say they’re always tired, even before other symptoms show up.When to Act: Timing Is Everything

One of the biggest mistakes in valve disease is waiting too long. If you have severe aortic stenosis and wait until you’re symptomatic, your two-year survival rate plummets to 50%. But if you get the valve replaced before symptoms hit, survival jumps to 85%. Doctors don’t operate just because a valve is narrowed. They look at three things: how bad the narrowing is, whether the heart is struggling, and whether you’re having symptoms. For asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis, guidelines say to monitor with echocardiograms every 6 to 12 months. If the pressure gradient hits 50 mmHg or more, or if tests show the heart is starting to weaken, it’s time to talk about replacement. For regurgitation, it’s the opposite. You don’t fix a leaky valve just because it’s leaking. If the heart is still strong and you have no symptoms, watchful waiting is often the right call. But if the left ventricle starts to enlarge or the pumping function drops below 60%, surgery becomes urgent-even if you feel fine. The key is catching it early. Many patients say they were dismissed by doctors until they were barely able to walk. A 2022 survey found 28% of valve disease patients felt ignored until their symptoms became severe. That’s why knowing your risk matters. If you’re over 65, have a family history of valve disease, or had rheumatic fever as a child, get an echocardiogram.

Surgical Options Today: From Open Heart to Tiny Catheters

For decades, open-heart surgery was the only option. A surgeon cuts through the sternum, stops the heart, and replaces the valve with a mechanical or tissue valve. It works-10-year survival for mitral valve replacement is 90%-but recovery takes months. Many patients say the sternotomy pain was worse than the valve problem itself. Now, there’s another way: transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Instead of opening the chest, a catheter is threaded through the groin or chest wall to deliver a new valve inside the old one. The procedure takes about 90 minutes, and most patients go home in 2-3 days. TAVR used to be only for high-risk patients. But now, it’s the first choice for most people over 75. In the US, 65% of aortic valve replacements in that group are done with TAVR. The PARTNER 3 trial showed TAVR patients had 12.6% lower mortality at five years than those who had open surgery. For mitral valve disease, options are expanding too. The MitraClip is a tiny device that clips the leaking leaflets together. It’s not a replacement-it’s a repair. The COAPT trial showed it cut death rates by 32% in patients with functional mitral regurgitation compared to medicine alone. For primary mitral regurgitation (where the valve itself is damaged), surgical repair still has better long-term results. New devices are coming fast. The Evoque valve, approved in 2023, is the first transcatheter option for the tricuspid valve. The Cardioband and Harpoon systems are in late-stage trials, aiming to fix mitral regurgitation without opening the chest at all. By 2030, experts predict 80% of valve procedures will be done this way.Choosing a Valve: Mechanical vs. Tissue

If you get a replacement valve, you’ll choose between two types: mechanical or tissue. Mechanical valves last forever. But you’ll need to take blood thinners-usually warfarin-for the rest of your life. That means regular blood tests (INR levels), avoiding certain foods, and being careful about falls or injuries. The target INR is 2.0-3.0 for aortic valves and 2.5-3.5 for mitral valves. Tissue valves come from pigs, cows, or human donors. They don’t require lifelong blood thinners, which is great for older patients or those at risk of bleeding. But they wear out. About 21% fail by 15 years. For patients over 70, that’s usually fine. For someone in their 50s, it might mean another surgery down the road. Newer tissue valves are designed to last longer. Some are already showing 25-year durability in early studies. If you’re young and active, your doctor might suggest a mechanical valve. If you’re older or don’t want to take blood thinners, a tissue valve is often the better fit.

mike tallent

November 17, 2025 AT 12:30