You don’t catch “more bugs” with obstructive lung disease by bad luck. The disease re-wires your defenses-right down to the cilia, mucus, and immune cells-so viruses and bacteria get a head start and flare-ups snowball. Here’s the plain-English version of what’s going on and what actually helps. I’m writing this from smoky, windy Sydney, where one dusty day can flip sensitive lungs from fine to flaring.

- TL;DR: Obstructive lung disease (mainly COPD) disrupts both frontline (innate) and targeted (adaptive) immunity, making infections and inflammation more likely.

- Expect more flares in winter, after smoke exposure, and during viral waves. Vaccines, smoking cessation, and good inhaler use give the biggest wins.

- Track blood eosinophils: higher counts predict steroid benefit but also call for infection vigilance; lower counts lean toward antibiotics/bronchodilators for flares.

- Daily habits (pulmonary rehab, airway clearance, sleep, nutrition) quietly recalibrate immunity and reduce hospital visits.

- Use an action plan: when symptoms jump, start your pre-agreed steps early; delays cost lung function.

What obstructive lung disease does to your immune system

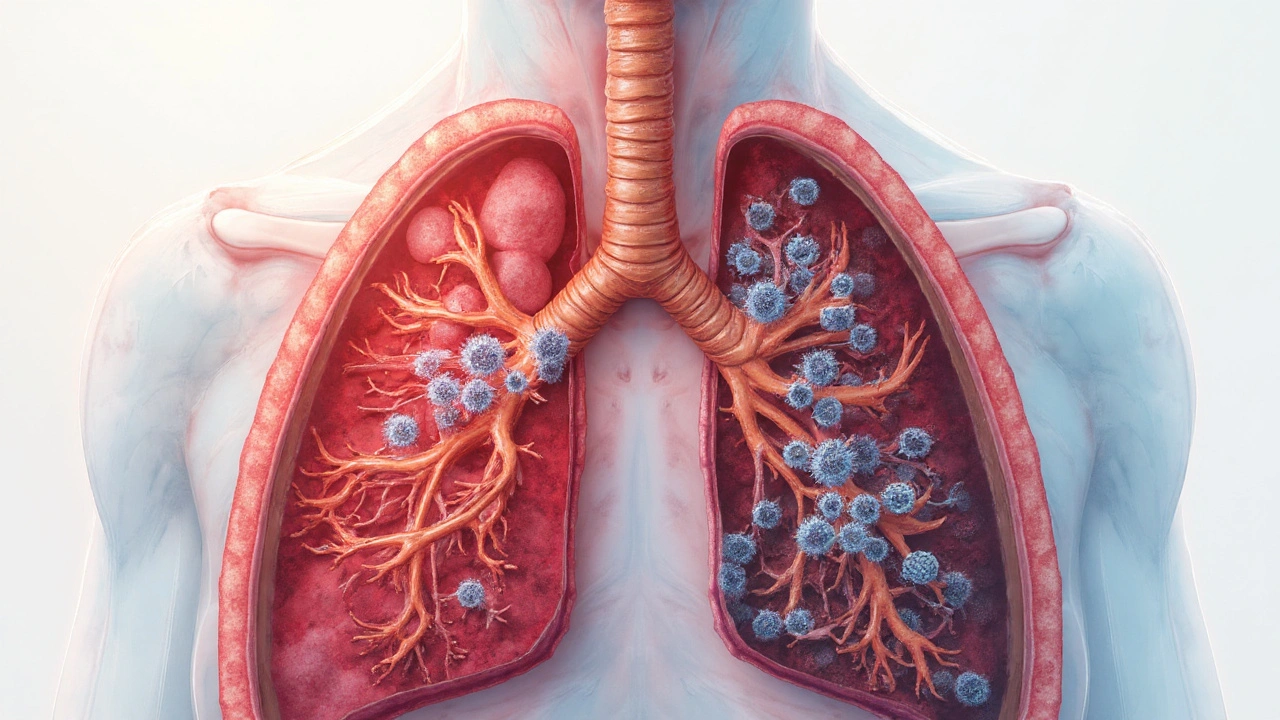

Obstructive pulmonary disease is a cluster of conditions where airflow out of the lungs is limited. That includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and in some people, asthma with fixed obstruction or bronchiectasis overlap. The common thread: stubborn air trapping and chronic airway inflammation that keep the immune system on a low, hot simmer.

Frontline defenses (innate immunity) change first. The airway lining makes thicker, stickier mucus; cilia beat less efficiently; and the epithelial barrier loses some of its tightness. That’s like turning a moving walkway into a muddy path-bugs don’t get swept out, and irritants hang around. Lung macrophages, the vacuum cleaners that should engulf bacteria and debris, get sluggish under the constant smoke, pollution, and oxidative stress. Neutrophils surge in, release enzymes and ‘nets’ to trap microbes, but those same tools nick healthy tissue and slow repair. GOLD 2025 and a 2023 Lancet review describe this “hyper-inflamed but under-effective” pattern well.

Targeted defenses (adaptive immunity) also shift. T cells skew toward Th1/Th17 responses, sustaining neutrophil-heavy inflammation. In some people, tertiary lymphoid follicles form in the airway walls-little immune bunkers that may maintain inflammation even without active infection. B cells pump out antibodies, but not always the helpful kind; there’s evidence of autoantibody activity in subsets of COPD, especially with severe emphysema. Studies in Nature Medicine (2022) and subsequent translational work indicate this chronic, misdirected fire contributes to airway remodeling and the permanent “obstructive” pattern on spirometry.

Microbiome changes amplify the problem. The lower airways in many patients shift toward colonization by Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and in advanced disease or bronchiectasis overlap, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. That doesn’t always cause fever or an obvious infection, but it primes flares. When a common cold virus (rhinovirus), influenza, RSV, or SARS‑CoV‑2 shows up, the fuse is short. Viral hits also open the door to bacterial superinfection. That’s why winter and crowded indoor settings matter, and why a couple of smoky days in Sydney or a dust storm out west can bring on a bad week.

Systemic spillover is real. Inflammatory molecules like IL‑6 and CRP climb and don’t completely settle. The body responds with higher clot risk, muscle loss, and bone thinning. You’ve probably heard someone say, “COPD is a lung disease with whole-body consequences.” Immunology is the bridge: chronic airway inflammation keeps the whole system on alert, and that’s exhausting.

Where do steroids fit? Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) calm eosinophil‑driven inflammation and reduce exacerbations in people with higher blood eosinophils (rough guide: consistently ≥300 cells/µL is a strong yes, 100-300 a cautious maybe, and <100 usually a no). But ICS can also raise pneumonia risk, especially in older adults with low eosinophils or a history of recurrent pneumonias. That’s the trade‑off: targeted immune dampening that helps the right subgroup, harms the wrong one. GOLD 2025 leans hard on tailoring ICS to eosinophils and exacerbation history.

What about newer options? Long‑term macrolides (like azithromycin) can reduce exacerbations in frequent-flare patients by modulating immune signaling and taming certain bacteria, but cost resistance and QT risks. Roflumilast, an anti‑inflammatory pill for chronic‑bronchitis phenotype with frequent flares, trims exacerbations at the price of GI upset and weight loss. And a 2024 NEJM trial followed by regulatory moves showed dupilumab can help a subset of COPD with type 2 (eosinophilic) inflammation; discuss local eligibility and coverage with your respiratory physician if your eosinophils run high despite best inhaled therapy.

Smoking and pollution sit upstream of all this. Tobacco smoke blunts macrophage function, drives oxidative stress, and keeps neutrophils flooding the scene. Air pollution, especially fine particles from traffic or bushfires, gives similar signals. The immune system reads those cues as “keep fighting,” even when there’s no real invader, and gets worse at fighting when a real invader arrives.

Here’s a simple way to picture it: protective barriers are thinner, brooms are slower, alarms ring constantly, and the firefighters are overworked. When a spark lands-virus, cold snap, smoky day-the blaze runs fast.

| Immune change | Real‑world effect | How it shows up | What helps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thick mucus + slow cilia | Poor clearance of microbes/irritants | Sticky sputum, morning cough, infections that “linger” | Hydration, airway clearance, mucolytics in select cases, avoid smoke |

| Sluggish macrophages | Harder to mop up bacteria/virus debris | Frequent bronchitis, colonization | Smoking cessation, vaccines, exercise, nutrition |

| Neutrophil‑heavy inflammation | Tissue damage, remodeling | Worsening airflow, purulent sputum during flares | Bronchodilators, macrolides (selected), roflumilast (CB phenotype) |

| Eosinophilic activity (subset) | ICS‑responsive flares | Frequent steroid‑responsive exacerbations | ICS when eosinophils higher; consider biologics if appropriate |

| Microbiome dysbiosis | Colonization, superinfections | Recurrent H. flu / Moraxella, occasional Pseudomonas | Vaccines, judicious antibiotics, airway hygiene |

What to do about it: steps, checklists, and real‑life playbooks

The wins come from small, boring things done consistently plus a few smart, targeted decisions. Here’s a simple framework that respiratory teams in Australia and beyond use daily.

Step 1 - Remove the constant triggers

- Stop smoking: ask for a script‑supported plan (dual NRT, varenicline, or combination therapy). In Australia, nicotine vaping is prescription‑only-talk to your GP if it’s part of your quit strategy.

- Air quality: on high‑smoke or high‑PM2.5 days (think bushfire haze), stay indoors with windows closed and run a HEPA purifier in the room you use most. A well‑fitting mask (P2/N95) helps outdoors.

- Work exposures: if dust or fumes are part of your job, ask about fit‑tested respirators and better ventilation.

Step 2 - Fortify the immune front line

- Vaccines: yearly influenza, up‑to‑date COVID‑19 boosters, and a modern pneumococcal schedule (PCV20 as a single dose, or PCV15 followed by PPSV23). In Australia, the National Immunisation Program funds these for eligible adults with chronic lung disease; ATAGI guidance is updated yearly.

- Pertussis booster (if >10 years), shingles vaccine at the recommended age band, and RSV vaccine when available for your age/risk group.

- Hand hygiene and avoid sick contacts during viral surges. It feels basic because it works.

Step 3 - Optimise inhaled therapy and tailor steroids

- Get your inhaler type and technique checked. Spacers help with MDIs; dry powder inhalers need a strong inhalation-ask for a demonstration.

- Long‑acting bronchodilators (LABA/LAMA) are the backbone. Add ICS if you’ve had ≥2 moderate or ≥1 severe exacerbations and your eosinophils run higher (roughly ≥300 cells/µL). Borderline counts (100-300): consider ICS if flares persist despite dual bronchodilators. Low counts (<100): avoid routine ICS because pneumonia risk rises without much benefit.

- If you’re still flaring: discuss azithromycin prophylaxis (ECG and hearing checks) or roflumilast for chronic‑bronchitis phenotype. Suspect asthma‑COPD overlap or type 2 inflammation? Ask if biologics are appropriate.

Step 4 - Build resilience with rehab, movement, and sleep

- Pulmonary rehab: 6-12 weeks of guided exercise and education improve fitness, reduce flares, and recalibrate immune tone. Ask for a referral; many programs in NSW run group and home‑based options.

- Exercise rule of thumb: aim for 150 minutes/week if you can, broken into short bouts with breathing control (pursed‑lip breathing, interval pacing). More muscle means better immune function and fewer bed days after a flare.

- Sleep 7-8 hours. Poor sleep is a known immune drag. If you snore or stop breathing at night, get assessed for sleep apnea-it’s fixable and it helps daytime breathlessness.

Step 5 - Keep mucus moving

- Daily airway clearance if you’re a “sputum maker”: huff coughing, active cycle of breathing, or an oscillatory device (Acapella/Flutter). A physiotherapist can match the technique to your lungs.

- Hydration and, for select people, mucolytics (carbocisteine or N‑acetylcysteine) can make sputum easier to shift. Evidence is mixed; base it on your pattern of flares and your clinician’s advice.

Step 6 - Eat for immune support, not magic

- Enough protein (1.2-1.5 g/kg/day if you’re losing muscle) supports antibodies and immune cells. Greek yogurt, eggs, tuna, legumes are easy wins.

- Vitamin D if you’re deficient; test, don’t guess. Zinc helps if you’re low; mega‑doses and “immune boosters” rarely help and often upset your gut.

- Keep reflux under control; micro‑aspiration irritates the airways and primes flares.

Step 7 - Act fast during a flare (your written plan)

- Recognise your early signs: increased breathlessness, more frequent rescue puffs, sputum turning green/brown, feverish or viral symptoms.

- Day 0-1: start your plan-rescue inhaler more regularly, add your prescribed oral steroids if indicated, and begin antibiotics only if you have signs of bacterial infection (purulent sputum or fever). If you keep an emergency antibiotic pack, use it as your plan advises-not for every tickle.

- Day 2-3: if no improvement or worsening, call your GP or respiratory clinic. Go to ED for severe breathlessness at rest, blue lips, confusion, chest pain, or oxygen saturation dropping below your usual baseline.

Quick checklists you can pin to the fridge

- Daily: take inhalers correctly, quick walk with pacing, airway clearance if sputum, drink water, sleep aim 7-8 h.

- Weekly: check air quality forecast; plan indoor exercise on smoky/windy days.

- Seasonal: flu shot, COVID booster if due, review action plan, refill rescue meds.

- Annual: spirometry, inhaler technique review, blood eosinophils, vaccine status, bone health if on steroids.

| Vaccine (Australia, 2025) | Who/When for obstructive lung disease | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Influenza | Every year, all adults with chronic lung disease | Best taken before winter; reduces hospitalisations |

| COVID‑19 | Boosters per ATAGI (age/risk dependent) | Higher risk groups may need more frequent boosters |

| Pneumococcal | Either PCV20 once, or PCV15 then PPSV23 (timing per ATAGI) | Funded for eligible adults with chronic lung disease |

| Pertussis (dTpa) | Every 10 years or for close infant contact | Consider earlier if an outbreak or household exposure |

| Shingles | At recommended age bands (usually 50+ and 65+ programs) | Reduces severe shingles and post‑herpetic neuralgia |

| RSV (when available) | Older adults at risk, as per 2025 guidance | Rollout and funding vary by state and season |

Two quick stories. A reader from Parramatta messaged that he was always sick after visiting grandkids. He moved grandkid hangs outdoors on mild days, masked up during daycare bug weeks, and switched to video calls when they were snotty. Flares dropped in half. At home, my wife Natalie and I watch air quality like we watch rain radar; on high‑smoke days, we run the purifier and move workouts indoors. It’s not glamorous, but it keeps our lungs happier.

Quick answers, red flags, and what to do next

Why do I get more chest infections than my friends?

Your airway broom (cilia) is slower, the mucus is stickier, and the immune cells are tired. Bugs hang around longer and multiply. Add a virus, and everything accelerates. That’s typical in obstructive lung disease and well‑described in GOLD 2025 and recent immunology reviews.

Do inhaled steroids “wreck” my immune system?

They tune it down in the airways, which is good if your flares are eosinophil‑driven and frequent. They can raise pneumonia risk, especially with low blood eosinophils. The trick is matching the medicine to the biology-your eosinophil count, flare history, and pneumonia risk. Don’t stop a prescribed ICS abruptly; discuss with your clinician.

Should I take antibiotics preventively?

Not by default. Long‑term azithromycin can help frequent exacerbators, but you need heart rhythm checks, ear checks, and a conversation about antibiotic resistance. For most people, antibiotics are for flares with clear bacterial signs: more breathlessness plus purulent sputum, fever, or raised CRP. A pre‑agreed “rescue pack” can be smart-used with rules, not feelings.

Do masks and air purifiers make a real difference?

Masks reduce exposure to viruses and smoke particles when fitted well. HEPA purifiers cut indoor particles on bad air days. Neither fixes disease, but both reduce immune aggravation, which lowers flare risk.

Is asthma the same as COPD for immunity?

Some overlap, some differences. Asthma is often type 2 (eosinophilic) inflammation and tends to be very steroid‑responsive; COPD leans neutrophilic and infection‑prone with structural changes. People with asthma‑COPD overlap may benefit from both COPD strategies and, in select cases, biologics.

What tests should I ask for?

- Spirometry (at baseline and yearly), oxygen saturation.

- Blood eosinophils to guide ICS decisions.

- Alpha‑1 antitrypsin level once if you had early/emphysema or a family history.

- Sputum culture if you have frequent purulent flares or bronchiectasis features.

- Chest imaging if symptoms don’t match spirometry or you’re worsening fast.

Can supplements “boost” my immune system?

Eat enough protein, correct vitamin D deficiency, and keep zinc normal. Beyond that, save your money. Echinacea, mega‑vitamin cocktails, and high‑dose antioxidants haven’t shown meaningful benefits for COPD flares in solid studies. Pulmonary rehab beats any pill here.

Does exercise risk triggering flares?

Hard, unpaced efforts can, but structured, paced training reduces future flares and makes you more resilient. Use interval walking, pursed‑lip breathing, and rest breaks. If you get wheezy with exertion, a pre‑exercise bronchodilator helps.

How has COVID‑19 changed things in 2025?

Two things: persistent viral waves in winter and better tools. Keep vaccines current, test early when sick, and use antiviral treatment if eligible. Many hospitalisations are preventable with early action and a good plan.

Next steps based on where you are

- Newly diagnosed, still smoking: book a quit plan with your GP, start dual bronchodilators if indicated, get your vaccines up to date, and ask for a pulmonary rehab referral. Put an action plan in writing.

- Frequent flares (≥2 per year): check eosinophils; consider adding ICS if high, or macrolide/roflumilast pathways if low eosinophils and chronic‑bronchitis phenotype. Review inhaler technique and do a sputum culture.

- Sputum every day, coarse crackles: rule in/out bronchiectasis with CT. Airway clearance becomes a daily prescription; antibiotic strategy may change.

- High eosinophils despite triple inhalers: discuss biologics eligibility with your respiratory physician.

- Rural or limited access: ask about tele‑rehab, home‑based programs, and mail‑out spacers/purifiers. Keep a home pulse oximeter and rescue plan on the fridge.

Red flags that mean “don’t wait”

- Severe breathlessness at rest or speaking in single words.

- Blue lips or fingertips, confusion, chest pain.

- Oxygen saturation dropping well below your usual baseline and not recovering with rest.

Evidence and where it comes from

The immune patterns and treatment guidance here reflect the GOLD 2025 report, ATS/ERS statements on exacerbations and bronchiectasis, a 2023 Lancet review of COPD immunopathology, and trials of macrolides, roflumilast, and dupilumab reported in major journals between 2011 and 2024. Vaccine advice reflects ATAGI 2025 guidance and the Australian National Immunisation Program. If any of those change, your plan should too-medicine moves fast.

If you remember one thing: you can’t white‑knuckle your way through obstructive lung disease. You lower the immune “noise,” you prepare for the hits, and you act early. The result is fewer flares, fewer antibiotics, and more days where you can do the stuff you actually care about.

Paul Koumah

August 28, 2025 AT 22:53