Switching from a brand-name NTI drug to a generic version sounds simple-cheaper, same active ingredient, right? But for drugs with a Narrow Therapeutic Index, that small change can mean the difference between stable health and a life-threatening event. NTI drugs have a razor-thin margin between the dose that works and the dose that harms. Even a 10% shift in blood levels can trigger seizures, organ rejection, dangerous bleeding, or toxic buildup. And yet, across the U.S., these switches happen daily, often without warning or extra monitoring.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

An NTI drug isn’t just any powerful medication. It’s one where the gap between the minimum effective concentration and the minimum toxic concentration is tiny-often less than a two-fold difference. Think of it like walking a tightrope: too little, and the treatment fails. Too much, and you risk serious harm or death.

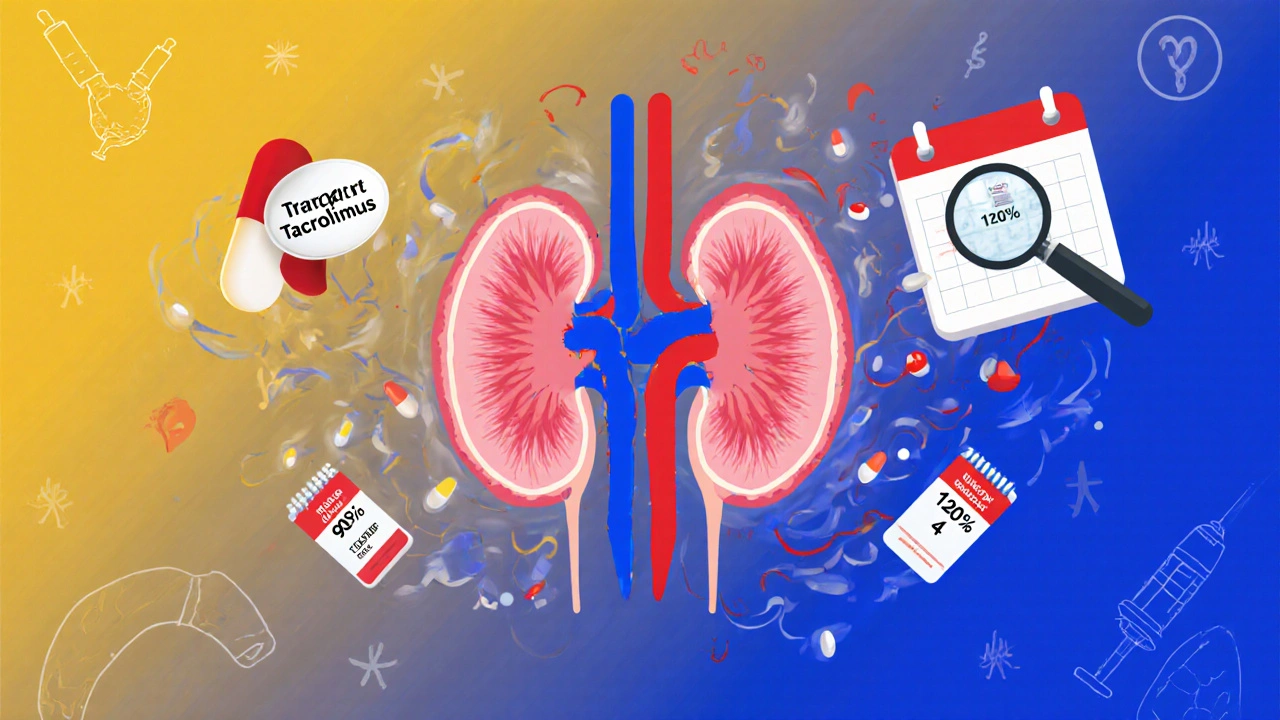

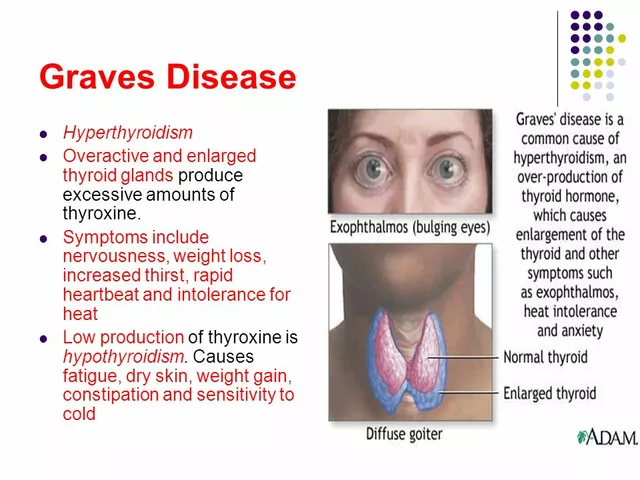

The FDA defines NTI drugs as those where small changes in dose or blood levels can lead to life-threatening outcomes or permanent disability. Common examples include warfarin (blood thinner), phenytoin and levetiracetam (anti-seizure meds), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), digoxin (heart medication), and cyclosporine and tacrolimus (transplant drugs). These aren’t optional medications-they’re essential for survival or preventing catastrophic events.

For most drugs, bioequivalence is measured by whether the generic delivers 80% to 125% of the brand’s blood concentration. That’s a 45% range. For NTI drugs, that’s far too wide. A patient switching from a generic at 80% to another at 125% could see their drug levels jump by over 50%-enough to push someone from safe to toxic without any change in dosage.

What Do Real Studies Show About Generic Switches?

Studies on NTI drug switches don’t tell one clear story. The data is messy, conflicting, and often depends on the drug-and the patient.

For warfarin, the most commonly switched NTI drug, observational studies show spikes in INR levels after a generic switch. One study found only 28% of patients stayed within 10% of their target INR after switching. Nearly 40% had worse control, requiring urgent dose changes. But randomized trials? They show no significant difference in bleeding or clotting events between brand and generic warfarin. So why the disconnect? Real-world switching often involves multiple generic brands over time, inconsistent manufacturing, and poor monitoring. The real risk isn’t the generic itself-it’s the lack of follow-up.

Antiepileptic drugs like phenytoin and levetiracetam tell a darker story. A review of 760 epilepsy patients found many switched to generics and then back to brand within months because of increased seizures, blurred vision, memory loss, and mood swings. One study showed generic phenytoin delivered 22% to 31% less drug in the blood than the brand. In another, 50 patients had breakthrough seizures after switching-nearly half had lower drug levels at the time of seizure. Neurologists often refuse to switch these patients unless absolutely necessary. In 73% of U.S. states, laws even require prescribers to write "do not substitute" on prescriptions for antiepileptics.

Immunosuppressants like cyclosporine and tacrolimus are critical for transplant patients. One study found 17.8% of patients needed a dose adjustment after switching from Neoral to generic cyclosporine. Trough levels jumped from 234 ng/mL to 289 ng/mL in just two weeks-enough to cause kidney damage or rejection. Tacrolimus showed better bioequivalence in studies, but even here, different generic brands varied widely. One manufacturer’s product ranged from 86% to 99% of the brand’s concentration. Another’s went from 100% to 120%. That’s not consistency-it’s unpredictability.

Levothyroxine is another battleground. Patients with hypothyroidism need stable hormone levels. A switch can cause fatigue, weight gain, heart palpitations, or even heart failure. While some studies show no clinical difference, others report patients needing dose changes after switching. The FDA itself has acknowledged that even minor formulation differences in levothyroxine can affect absorption-especially when switching between generics made by different companies.

Why Do Some Patients Do Fine and Others Don’t?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person.

Some patients switch from brand to generic and never notice a difference. They’re stable, their labs stay in range, and they feel fine. Others? They crash. Why?

One reason is variability in how the body absorbs drugs. Some people have slow gut motility. Others have stomach acid issues or take medications that interfere with absorption. A generic that works perfectly for one person might not dissolve the same way in another. This is especially true for drugs like levothyroxine, which are sensitive to food, timing, and other pills.

Another factor is manufacturing. Generic drugs must meet FDA standards, but those standards don’t require identical inactive ingredients, coating, or dissolution rates. One study found that different generic versions of tacrolimus varied in active ingredient content by more than 20%. That’s not a typo-it’s a 20% difference in how much drug actually gets into the bloodstream. When you’re on a drug where 10% can be dangerous, that’s a huge problem.

And then there’s the issue of switching between generics. A patient might start on Brand A, then switch to Generic 1, then Generic 2, then Generic 3-all AB-rated, all technically "equivalent." But each switch adds another variable. No one tracks which version they’re on. No one checks levels after each change. That’s when things go wrong.

What Do Pharmacists and Doctors Really Think?

Pharmacists are on the front lines. A national survey found 82% would still substitute generic NTI drugs. But here’s the catch: 41% said they recommend extra monitoring after the switch. For antiepileptics, that number jumped to 62%. Many pharmacists quietly warn patients: "If you start feeling off, call your doctor. Don’t wait."

Doctors, especially neurologists and transplant specialists, are far more cautious. Many refuse to switch patients on NTI drugs unless there’s a clear financial hardship-and even then, they insist on close follow-up. Some only allow switches if the patient has been stable for over a year and has access to frequent lab testing.

The FDA says AB-rated generics are therapeutically equivalent. But they also admit: "For NTI drugs, tighter bioequivalence standards may be warranted." That’s not a strong endorsement. It’s a warning.

What Should You Do If You’re on an NTI Drug?

If you’re taking an NTI drug, here’s what you need to know:

- Know your drug. Is it warfarin? Levothyroxine? Cyclosporine? These are high-risk. Don’t assume generics are interchangeable.

- Ask your pharmacist. When you pick up your prescription, ask: "Is this the same brand as last time?" If it changed, ask if they can keep you on the same one.

- Request a "do not substitute" note. You have the right to ask your doctor to write "dispense as written" or "do not substitute" on your prescription. Many states allow this for NTI drugs.

- Monitor closely after any switch. If you’re on warfarin, get your INR checked within 3-7 days after switching. If you’re on levothyroxine, get a TSH test in 6-8 weeks. For transplant drugs, your doctor should check levels at 2 and 4 weeks.

- Track your symptoms. Did you start feeling more tired? More anxious? Have more seizures? Notice swelling or bruising? Don’t brush it off. Call your doctor immediately.

Don’t let cost savings come at the cost of your health. If your insurance pushes a generic you’re not comfortable with, appeal it. Many insurers will approve brand-name drugs for NTI medications if you document the risk.

The Bigger Picture: Where Is This Headed?

The FDA is starting to wake up. In 2022, they released draft guidance proposing product-specific bioequivalence standards for NTI drugs-not one-size-fits-all. That’s a big step. The European Union and Canada already use stricter standards: 90% to 111% instead of 80% to 125%. The U.S. is behind.

Post-marketing data shows NTI drugs make up only 5% of generic prescriptions but 18% of all generic-related adverse events. That’s a red flag.

In the next five years, experts predict a 15-20% increase in therapeutic drug monitoring for NTI drugs. That means more blood tests, more visits, more cost-but also more safety.

Meanwhile, research into pharmacogenomics is underway. The goal? To match patients to the right drug based on their genes. If your body metabolizes warfarin slowly, you might need a different dose than someone else-even if you’re on the same generic. This isn’t science fiction-it’s coming fast.

For now, the message is clear: NTI drugs aren’t like other generics. They demand attention, vigilance, and communication. If you’re on one, don’t just accept the switch. Ask questions. Demand monitoring. Protect your health like your life depends on it-because it does.

Are all generic drugs unsafe for NTI medications?

No, not all generics are unsafe. Many patients switch successfully without issues. But the risk is higher than with regular medications. The problem isn’t the generic itself-it’s the variability between brands and the lack of monitoring after a switch. Some generic versions are just as reliable as the brand. The key is consistency: once you find a generic that works, stay on it.

Can I ask my doctor to keep me on the brand-name NTI drug?

Yes, absolutely. You have the right to request that your doctor write "dispense as written" or "do not substitute" on your prescription. Many states legally allow this for NTI drugs like antiepileptics, warfarin, and immunosuppressants. Insurance may require prior authorization, but if you have a history of instability after switching, your doctor can usually justify keeping you on the brand.

How long should I wait before checking my blood levels after switching NTI generics?

It depends on the drug. For warfarin, check your INR within 3-7 days. For levothyroxine, wait 6-8 weeks before testing TSH. For cyclosporine or tacrolimus, your transplant team will likely want a blood test at 2 and 4 weeks after the switch. Never assume stability-always confirm with lab work.

Why do some states restrict generic substitution for antiepileptic drugs?

Because seizures can be deadly. Studies show a significant number of patients experience breakthrough seizures after switching to generic antiepileptics, even when bioequivalence standards are met. The risk isn’t theoretical-it’s documented in real patients. Seven out of ten U.S. states have laws requiring explicit permission from the prescriber before substituting these drugs, recognizing that the consequences of failure are too severe to leave to chance.

Is it safe to switch between different generic versions of the same NTI drug?

It’s not recommended. Even if each generic meets FDA standards, switching between different manufacturers can cause unpredictable changes in drug levels. One study found that different generic versions of tacrolimus varied in active ingredient content by up to 20%. That’s enough to push a transplant patient into toxicity or rejection. Stay on the same generic brand once you’ve found one that works.

Final Takeaway: Don’t Assume Equivalence

NTI drugs are not ordinary medications. They’re precision tools. A generic version might work fine-but only if you treat it like a controlled variable, not a commodity. The system is built for cost savings, not safety. That’s why you have to be your own advocate. Know your drug. Track your labs. Speak up when something feels off. Your life may depend on it.

Dana Dolan

November 20, 2025 AT 17:41